“You should never be in the dark with a map in your hand!”

You want to squeeze in an extra multi-pitcher on Gable Crag but it

takes longer than you thought. Someone in your team sprains their ankle

near the summit of Glyder Fawr and you have to snails pace it back to

Ogwen Cottage. At sunset you find your path blocked by fallen rocks and

the alternative route involves a 7km detour…

Although good planning and solid daytime navigation are your first

defence against getting caught out after dark, there’s still lots of

reasons why darkness can catch you out while still far from basecamp.

The problem is that darkness and disorientation are two primeval human

fears – throw in bad weather, injuries, or the threat of missing last

orders and it’s easy to see why so many mountaineers find it such a

daunting prospect.

So, how do you get back safely and efficiently when you can’t see past

the end of your torch beam and the shadows are making every contour

feature look like the Hilary step on Everest?

Luck favours the well prepared

Never leave the valley without a reliable headtorch. LED

torches have all but taken over nowadays and it’s not hard to see why.

The night vision friendly blueish light, fantastic reliability, battery

life the Duracell bunny would kill for and halogen comparable

performance all means you really don’t need to look any further.

There are loads of superb torches out there but there are a few key

features to look out for. Models with several light output levels help

conserve battery power and help avoid dazzling you when you’re looking

closely at the map. It’s also useful to have a beam that can be changed

between spot focus to help you pick out distant features and wide-angle

that’s ideal for illuminating the ground in front of you as you walk.

Good weather resistance is also important for our ‘interesting’ climate

and make sure the head attachment system is secure so it doesn’t keep

toppling off your head.

One thing that many torches seem to suffer from is fiddly control

buttons that are hard to use with cold fingers or when you have gloves

on. Take your Everest thickness mitts along and check the buttons out

in the shop – you may get some strange looks but you won’t regret it

when you’re descending An Teallach in the early hours and need to

quickly flick on your spot beam to see what lies ahead!

Having discussed torches it’s worth mentioning that navigators are

often very quick to flick their torch on at the first sniff of

darkness. Sometimes you can travel safely using moonlight instead and

it’s even better if there’s good snow cover too. Remember that once you

start using your torch you’re pretty much committed because your night

vision takes a long time to readjust if you turn it off again.

In terms of other equipment it helps if your compass has some of those

little luminous markers on and choose a watch with clear digits and a

stopwatch for timing distance. I also find an altimeter particularly

useful at night as it can help determine your position on features like

ridges and gently undulating featureless terrain. I

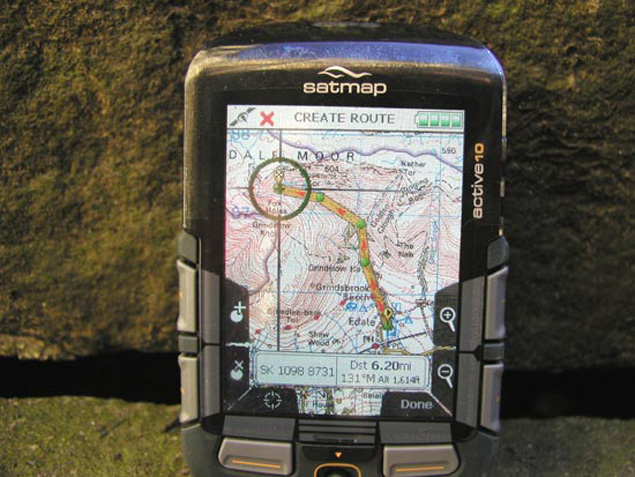

I’ve also often used a GPS when practising navigation as it can help to

confirm you have got where you want to go and also allows you to

relocate if you do find yourself ‘temporarily misplaced’ (also known as

lost!). I always replace the batteries in my torch and GPS before each

night navigation session and take a spare torch and batteries as well.

Don’t forget your extra map and compass, spare clothes and plenty of

food and drink too.

If you laminate map sections or use a map case try to find coverings

with a matt finish because some of the shiny plastic types really

bounce the light back. You can also reduce this effect slightly by

shining your torch onto the map from the side if it’s causing problems.

Remember to keep your torch away from your compass if you are holding

it in your hand though!

Practice makes perfect

I’m sure I’d be right in thinking you became proficient at daytime

navigation by practicing. Well, of course, that’s also the trick with

the night time version too. The problem is it takes a lot of motivation

to head out when you are missing East Enders or just got back from a

long day at work.

An easy way to get quality practice time in without the worry of having

to spend a night out is to go out a few hours before sunrise. That way

if you do get lost you can just wait for daylight to arrive. This also

means you can fit your night navigation practice into a longer walk.

For your initial forays choose an area with plenty of interesting

features to navigate between and a good relocation feature like a road

in case things go pear shaped. Once you are completely comfortable in

this sort of terrain you can up the ante and try more challenging

areas. It’s also worth choosing nights with good weather so you don’t

have too much to deal with at once.

It’s essential to carefully plan your route in advance and mark the

features onto your map with a marker pen. To do this effectively you

need to be sure you understand the way features are represented on the

map. How steep is that slope going to be? Will you end up at the top of

that cliff or standing at the bottom of that outcrop instead? Go with

someone else and don’t forget to leave a route plan with someone too.

Time goes by…so slowly

Madonna sang about it but I doubt she’s ever night navved across

Bleaklow! Most people feel time passes quicker than it actually does

when they’re estimating elapsed time at night. Trust your stopwatch and

don’t be tempted to ignore the information it’s providing. The more you

practice the less this will be an issue.

It’s also common to think you have travelled further than you have when

you are measuring distance by pacing. Practice will again allow you to

work out if your night paces are covering the same distance as your day

paces. Remember that pace length will also be affected by snowy

conditions and some terrain – try a night crossing of Kinder Plateau

after heavy rain and you’ll know what I mean!

While we’re talking about time I always consciously slow down my

decision making and double check all my calculations at night. I figure

the few extra minutes it takes is preferable to having to relocate

because I’ve rushed into a bad choice. It’s worth always getting your

partner to make their own calculations and compare the results too.

Inch by inch it’s a cinch, yard by yard its hard

I once sat in a motivational talk given, very bizarrely, by one of the

Power Rangers. One of the things he pointed out was that breaking

challenges down into small steps helps you to achieve your goals. Never

has that advice been more relevant than when navigating at night.

Two of your key night nav techniques are walking on compass bearings

and distance measurement (by timing or pacing). These techniques are

very accurate but they are also prone to error if you walk too far, not

far enough, or stray from your bearing. The best way to minimise the

risk of this happening is to break each navigational leg into smaller

sections than you would attempt in daylight. If you also use obvious

features to aim for you should still be able to work out where you

wanted to be even if you’ve gone a bit astray.

It’s also worth thinking of each navigational leg as a journey.

As you plan it on the map you can then identify individual features you

will ‘tick off’ on the way; the stream after 50 metres then the rocky

outcrop after 150 metres. Tick off features give you the confidence

that you are on track but also allow you to quickly address the problem

if the features you encounter doesn’t match your journey plan.

I followed a 176 for 150 then handrailed the wall to the attack point…

If you listen to a bunch of orienteers recounting their event you could

easily be mistaken for thinking you are listening to a different

language – they love jargon! But, once you actually fathom out the

terms they are using you’ll see they refer to navigational techniques

you already use all the time…

I use ‘attack points’ a lot at night. They are especially useful when

you are breaking a journey into small sections as mentioned earlier

(even though you may end up walking a bit further). Say the target you

want to find is 100 metres to the side of the end of the tarn you are

standing next too. Rather than take a long compass bearing directly to

it, you could walk around the edge of the tarn then use the bottom of

it as an attack point to the target. This makes it far more likely you

will get to the point you want whilst also allowing you to easily

retrace your steps if you don’t find it.

‘Handrails’ are linear features that can be especially useful at night.

They can be things like landscape features, streams, roads or walls and

are usually easily identifiable on your map and the ground. However, at

night it is essential that you use some handrails with great care as

they can follow dangerous terrain that you can’t see with your

headtorch. For example, streams that drop down steep gullies or ridge

lines with steep slopes on either side.

Try to choose features that also have a ‘catching feature’ beyond; I’ll

head for that stream junction but if I go too far I will come to the

wall 50 metres beyond. Similarly, a ‘gathering feature’ is two linear

features that join and can provide useful confirmation of your

location; I’ll follow the stream (linear feature) until I get to the

stream junction (gathering feature). Even better if you also have a

catching feature incase you go too far.

‘Aiming off’ is a useful way to avoid compass bearing deviations

turning into a major problem. For example, rather than trying to take a

compass bearing straight to that key wall junction, aim off by taking

the bearing straight to the wall right of the junction. Then once you

meet the wall you will know you just need to turn left and follow the

wall along.

In daytime you probably travel on your compass bearing by sighting

along your line of travel and picking terrain features to head for.

This is a great way to ensure you don’t stray from your bearing. You

can use the same method at night even though you won’t be able to use

features so far ahead; that tuft of grass at 50 metres then that small

rock after 30 metres etc. If the terrain is completely featureless you

can send your partner in front and sight on them – just make sure you

don’t lose each other!

Don’t panic!

Everyone gets temporarily misplaced sometimes – its how you deal with

it that really matters! The priority is to keep calm. It’s easy to

start panicking but there’s no more reason to be nervous at night than

there is in daylight. After all, the same things are there!

The strategies available to you are the same as those you’d use in

daylight although depending where you are you may even have the

advantage of spotting some car headlights or house lights in the

distance. Stop for a few minutes, study your map and the features

around you and make a plan. Having a drink and some food will also

provide a bit of comfort and feed your brain cells. Then, when you’re

ready, put your plan into action and see how it goes. If it doesn’t get

you where you want to go just make a new plan.

There really is nothing to fear about navigating at night. Infact it’s

a very liberating experience and you’ll feel a real buzz when you can

get around the hills safely and confidently in the dark. The other

advantage is you’ll almost certainly get the mountains to yourself! If

you want some extra input you can always book on a navigation course

although before you book it’s worth checking that a night navigation

element is included. If you can’t find a course that fits the bill most

instructors will be happy to run a session for you.

About the author

Paul Lewis is is the owner of Peak Mountaineering

and a Mountaineering Instructor. Peak Mountaineering offers a full range

of winter courses and full details can be found at

www.peakmountaineering.com.

Here’s his comprehensive take on crampon

selection, use, maintenance and more.